The Times wrote a good piece about e-waste and included our network’s data. All of your data is here, and it’s really helpful in making the point! Please share with volunteers.

Valuable metals go to waste in a tsunami of discarded electronics

Only a third of small electrical items are collected for recycling, official waste industry data reveals. It means households are wasting precious metals and other valuable materials they contain because people find it too difficult or cannot be bothered to recycle laptops, toasters, kettles, electric toys and other items which are broken or no longer wanted.

Recycling saves on the energy and land needed to mine new material and also reduces the risk of toxic chemicals, such as persistent organic pollutants in plastic, leaching out of landfill sites.

The number of electronic devices in homes has boomed in recent years and many are not built to last, creating what the House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee calls a “tsunami of electronic waste”.

The UK produces 24.9kg of e-waste per person per year, higher than the EU average of 17.7kg.

Brian Jones is employed to break open black bags brought to a council tip in Earlswood, Surrey, and pick out recyclable items. He removes about 30-40 electrical items a day.

“People can’t be bothered to separate their stuff for recycling — they just want to get rid of it and chuck it in the bin,” Mr Jones said.

He says he extracts as much as possible but cannot check every bag when the tip is busy.

He works for SUEZ, a waste company which removed 290 tonnes of electrical items from black bags at 11 tips in Surrey last year. Few other tips check black bags in this way as operators claim it is not cost effective any may be unsafe.

Producers of electronic products are required to pay into the Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Fund (WEEE Fund) which is used to increase recycling rates.

But the amount they pay is tiny — £3.5million in 2018 — compared to the billions of pounds spent on their products.

The UK missed its target, set under the EU’s waste electrical equipment directive, of collecting 45 per cent of e-waste in 2018. A total of 493,000 tonnes was collected, 44,000 tonnes short of the target.

Next month the industry will launch a major education campaign to try to persuade people to recycle their e-waste. Money from the WEEE Fund will be used to test a free bookable collection service from households. Scott Butler, the fund director, describes this as a “reverse parcel service”.

Only one in 10 homes has a regular doorstep collection of e-waste and Mr Butler said it needed to be made easier for people to recycle these items. From next year all major retailers of electronic products will be required to take back e-waste from customers.

But Mr Butler acknowledged that people might need an incentive to do the right thing and so the industry is planning reward schemes for schools and community groups that run e-waste collections.

“Currently we don’t recognise the value hidden in our old electricals, so we tend to just chuck them away,” Mr Butler said.

“We want to raise awareness of the fact that anything with a plug, battery or cable can be recycled.”

The problem would be much easier to solve if households did not produce so much e-waste in the first place.

Barry Walker, chief executive of SWEEEP, an e-waste recycling company in Sittingbourne, Kent, says the products he receives are getting younger.

“We see so many toasters and kettles that have lasted until the end of their warranty but not much longer,” he says.

“The focus of engineering and design has been to make things cheaper but that results in a much shorter life. There is also a trend in electronics for lightweighting — items are getting smaller and weaker.”

Mr Walker says his plant, which smashes up 150 tonnes of e-waste a day and extracts 30 different materials for recycling, also receives many products that are still working or have minor faults that could be repaired.

He tried working with Kent County Council on a scheme to collect and refurbish Dyson vacuum cleaners which were being thrown away because of a simple fault with the cable.

But he said the scheme was abandoned because the collection, repair and testing cost more than the £30 charged for a second-hand Dyson.

His plant dismantles 50,000 TVs and other screens a month, many of which were discarded though still in perfect working order because their owners were upgrading.

“People want the best ones and some are switching to OLED [TVs],” he said. “We are seeing a massive number of LED screens already coming in.”

Wrap, the waste reduction charity, estimated in 2017 that 38 per cent of the nine million new televisions sold annually replaced functional products.

SUEZ rescues and resells some working TVs for £20-50 at three “re-use shops” at its tips at Earlswood, Shepperton and Witley in Surrey.

It has sold 864 sets since 2017 but this is only a fraction of the TVs brought to its tips. It only has space in the small shops to display a few and says new TVs are so cheap anyway that there is limited demand for second-hand ones.

Sarah Ottaway, sustainability and social value lead at SUEZ, said the solution could lie in companies leasing products rather than selling them, with customers paying a fine if they fail to return them when broken or no longer wanted.

BT plans to save up to 1m wifi routers and set-top boxes a year from incinerators and landfill by introducing new contracts under which it retains ownership of equipment. Customers will have to pay up to £50 if they do not return it. Sky is also planning to expand its non-return charges.

Richard Kirkman, chief technology and innovation officer at Veolia, says the e-waste mountain is partly due to products becoming harder to repair.

Products are often glued together and can break when taken apart. Special tools are often needed to undo screws.

“One of the biggest game changers would be providing a code on the product so you can go to a website and get instructions on how to repair it,” he said.

“That’s difficult for manufacturers to accept because it means you are not going to keep buying new products.”

Manufacturers of electrical goods will be required to make repair manuals and spares available to professional repairers under new EU rules coming into force in April next year. However, people who want to carry out their own repairs may struggle to get the parts and information they need.

Back at the SWEEEP plant, Mr Walker is preparing for the annual surge in dumped garden electrical equipment, which occurs each spring when people get it out of the shed, find that it is not working and discard it without attempting repair.

“We are a society now that throws things away and buys another one,” he says.

Mr Walker thinks manufacturers should offer much longer warranties to force them to redesign products to last at least ten years.

“They do so much product testing they know exactly when it’s going to fail,” he said.

Case study

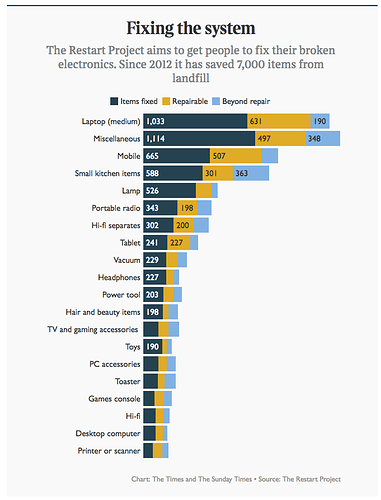

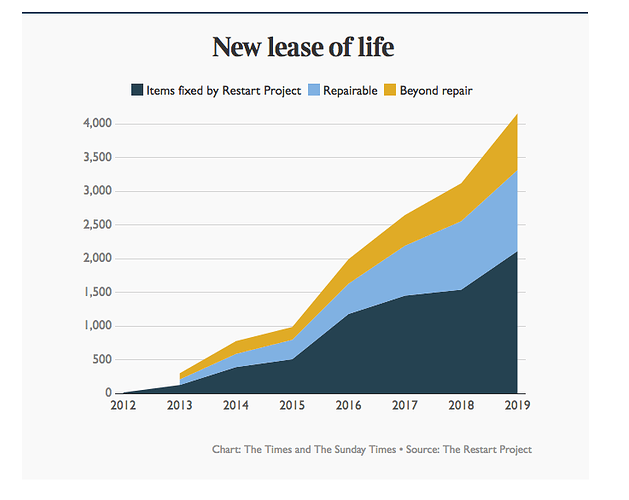

A scheme that began in Britain to curb electronic waste has spread to 12 countries and saved more than 7,000 items from landfill (Rosa Ellis writes).People are taking their broken laptops and iPhones to workshops and learning how to fix them as part of a project that started in London and takes place across the world from Tunisia and Canada to Italy and Iceland. Volunteers at the Restart Project have fixed more than 1,000 laptops, 600 mobile phones, 500 lamps and 200 tablets since it was established in 2012.

Janet Gunter, a co-founder, said: “We knew that people were frustrated with electronics but we didn’t know how many people wanted to help and share their skills. There are fixers everywhere, in every neighbourhood, in every street.”

Kettles appear to be the hardest to maintain, with 47 per cent deemed unfixable at the workshops. Laptops are among the easiest to fix, followed by musical instruments and lamps.

The UK fixers have their work cut out if they are to make a dent in the country’s mountain of e-waste. The UK generates 24.9kg of e-waste per person. The EU average is 17.7kg. The UK recycles 45 per cent of its e-waste.