Originally published at: https://therestartproject.org/repair-economy/recycling-wont-stop-premature-obsolescence/

This post from our co-founder Ugo Vallauri was originally published on Euroconsumers.

What is the goal of a true circular economy?

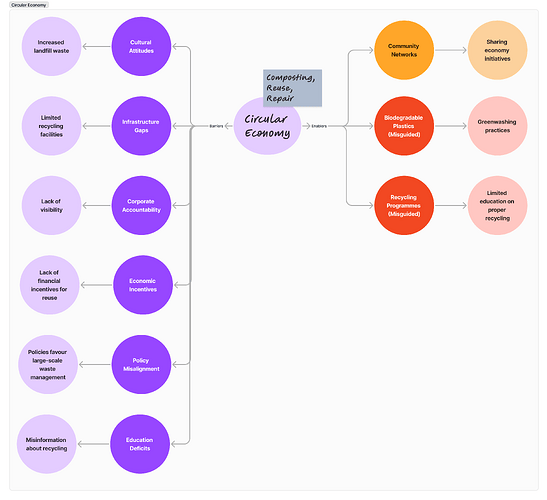

Depending on the actors involved, motivations can seem at times in contradiction with each other or lead to completely different objectives. Some argue that circularity is about ensuring that we recoup as many of the materials in the products we no longer use so that they can be used to manufacture new devices and appliances. Others concentrate on the importance of pushing ahead with legislation making future products more repairable as well as energy-efficient.

Fixing our relationship with electronics by resisting obsolescence

These are all important aspects, but what about all of the products that have already been manufactured and are still in use? For this, fixing our relationship with electronics is key, and this has been The Restart Project’s tagline since our inception.

From day one, at our very first Restart Party back in 2012, we’ve supported community approaches towards extending the life of existing products: resisting obsolescence by sharing knowledge, skills and creating alternative solutions where they didn’t seem to exist. Our primary focus is consumer products, small electricals and electronics.

Why this focus? Electrical waste (e-waste) is one of the fastest growing waste streams globally.

It was estimated that 62 million tonnes were produced globally in 2022, an increase of 80% since 2010.

One third of this waste (20.4 million tonnes) is small devices, the products we see at community repair events.

Only 12% of these are recycled globally.

While recycling rates are higher in Europe, repair can help to cut this waste by keeping items working longer.

What’s the role of recycling?

Recycling is important – but only when repair and reuse are no longer possible.

In 2023, we tested 600 products taken to a recycling centre in London, and we learned that shockingly almost half of those sent to be shredded for recycling could have been reused instead.

Earlier this year together with members of our community, we researched all recycling centres in the UK , and discovered that less than 1 in 5 ( 19%) of them offer reuse options for the electrical and electronic products that residents bring in.

While products should be correctly recycled at the end of their lifetime, many should be living a longer – or a second, third life – in the hands of people that can use them, before they reach the bin.

By focusing so heavily on recycling, we are missing opportunities to reduce waste, lower climate emissions associated with manufacturing new products, while saving households money.

For many of the products we use, the vast majority of the environmental impact occurs during the manufacturing phase: for a smartphone for example, up to 80% of the overall impact is before you’ve ever switched it on. And current recycling technologies can only recoup a small amount of some of the materials.

A circular vs a linear electronics economy

So, what could a circular economy for these products look like, compared to what we have now?

- Manufacturers should proudly be offering affordable repair options, learning from best practice by independent repairers. Giving consumers the choice of genuine, compatible or even used spare parts. Instead, when you try to get a product repaired, you’re often told you should upgrade to a more modern product instead – it’s happened to me multiple times this year alone.

- Mobile operators, and other retailers, should reward slower approaches to consumption, for example by giving tangible discounts and benefits to people not upgrading their device. Instead, there still seems to be a gold rush to win over new customers by offering the opportunity to change device every 3 (!) months. (1)

- Marketplaces should be clear and transparent not just about their return policies, but also their return practices, for example by committing to resell or donate any unsold or returned product. Instead, we keep hearing and seeing reports of products destroyed or sent to recycling once they’re returned (2), because it’s less expensive than having them checked and prepared for reuse.

- Recycling centres should become reuse centres first: filtering products to be reused as much as possible, while creating opportunities to salvage reusable spare parts for products no longer repairable. Instead of losing tonnes of functioning products and parts that could be reused.

- Consumers should pledge to repair their products, keep them in use for longer before upgrading, choose refurbished second hand products rather than brand new ones, whenever available. Businesses as well as public authorities should be required to do the same, and should be transparent about their policies.

Measure for circularity

We also need new targets and indicators to help us measure the shift to a more circular economy. A good example is Goal 12 of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals: Responsible Consumption and Production. Among its targets is 12.5 “Substantially reduce waste generation” by 2030 through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse.

The only indicator currently included to check on progress is the increase in recycling. Sure: we need to recycle more – and better – rather than sending products to landfill. But we should also recycle later, at the very end of a product’s useful lifetime.

And we should measure how much we repair, reuse, and prevent unnecessary manufacture and purchasing of new products, if we’re serious about reducing our environmental footprint.

So, while we keep pushing for ambitious right to repair legislation via the Right to Repair Europe coalition, we should make sure that the future Circular Economy Act focuses on reusing, repairing and not just improving recycling rates of e-waste.

—

References:

(1) As still advertised for example by O2 in the UK at the end of 2024: https://www.o2.co.uk/o2-switch-up

(2) This report by the European Environmental Bureau lists a wide range of proofs of the amount of unsold electronics destroyed across Europe: https://eeb.org/library/note-on-the-destruction-of-unsold-electronics/

Featured photo: Mark A Phillips